The Takeaway: The latest iteration of the avian flu is grabbing headlines and prompting caution in the United States and around the world. H5 bird flu is common in wild birds globally but is currently causing outbreaks in poultry and dairy cows, and now cases are spreading to dairy workers in the U.S. IDT has responded quickly to this outbreak, offering a primer and probe set for the identification of Type A (H5) Clade 2.3.4.4b. Read on to learn more.

What is avian flu?

Avian influenza, also known as bird flu, is an infectious disease caused by viruses that mostly target wild birds. Wild aquatic birds like ducks, geese, and storks are most likely to catch this flu, though domestic poultry like chickens and turkeys can get it too. Symptoms include sudden death, low energy, swelling, reduced egg production, and nasal discharge, coughing or sneezing. Avian flu can also infect domestic and wild mammals such as dogs, cats, cows, bears, raccoons, and foxes. Symptoms in these animals can include fever, difficulty breathing, and death.

Can avian flu spread to humans?

Yes. While bird flu is mostly spread between birds, and from birds to other animals, there are cases of it spreading to humans. As of May 30, there have been four total reported human cases in the U.S., including three that occurred after exposure to dairy cows and one that occurred after exposure to poultry.

While bird flu is rare in humans, it’s a disease you want to avoid getting. Avian flu does not usually infect people, but there have been rare cases of human infection. Infections range in severity from unnoticeable to death.

Human infections with avian flu usually happen when the virus gets into your eye, nose, or mouth, or is inhaled. Guidelines for humans who might come into contact with the virus include:

- Wear personal protective equipment (PPE) when in direct or close contact (less than about 6 feet) with sick or dead animals like poultry or wild birds, or with other animals, litter, feces, or material potentially contaminated with the virus

- Those who come into contact with suspect animals, including those who were wearing PPE, should be monitored for new respiratory illness symptoms, including conjunctivitis, for 10 days after their last exposure

- Poultry farmers, poultry workers, livestock farmers and workers, veterinarians and vet staff, backyard bird flock owners, and emergency responders should avoid unprotecrted direct physical contact or close exposure with sick birds, livestock, or other animals; the carcasses of birds, livestock, or other animals; feces or litter; raw milk; and surfaces and water that might be contaminated with animal excretions

- Clinicians should keep in mind that there is a chance that there could be virus infection in people with signs or symptoms of acute respiratory illness who have relevant exposure history

- State health departments should be on alert and ready to notify the CDC if there’s a case under investigation

- There are also detailed recommendations for surveillance and testing

There is currently no evidence of human-to-human spread and the current public health risk, as assessed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is low. No human vaccines for avian flu exist in the U.S., and normal flu vaccines won’t work to protect you against avian flu.

Why is testing for avian flu important?

According to the CDC, there are currently nine states with outbreaks in cows, 48 states with poultry outbreaks, and bird flu is present in wild birds basically everywhere. To protect both human and animal health, testing is important.

There are two testing methods, depending on who or what is being tested—humans or poultry.

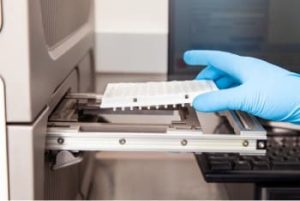

Bird flu tests for humans: A healthcare worker collects a nose or throat swab and sends it to a testing lab, which uses a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to get results in a few hours.

Bird flu tests for poultry: A bunch of tests can be used on poultry, including virus isolation, direct RNA detection, and an antigen capture immunoassay. Which test to use depends on different circumstances—for example, the immunoassay test is available commercially and can be good for screening flocks but is less sensitive than a molecular assay. Identified early enough, avian flu can be treated with antiviral meds.

What is avian flu clade 2.3.4.4b?

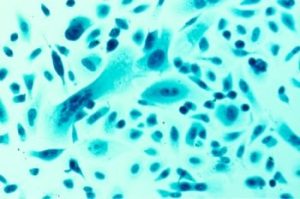

Avian influenza virus H5N1 has evolved over time into 10 clades and multiple subclades. These clades are defined based on their phylogenetic characterization and the sequence homology of the hemagglutinin gene.

The current clade in circulation is H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b. CDC has termed this clade “highly pathogenic” in dairy cattle and cats. This clade showed up in the U.S. in late 2021 and has been blamed for human disease in Ecuador and Chile. It made a resurgence in dairy cattle in the U.S. in the winter of 2024, affecting herds in Kansas, Texas, and New Mexico, as well as domestic cats that were fed raw milk from sick cows. More recent testing showed that “dairy cattle are susceptible to infection with HPAI H5N1 virus and can shed virus in milk and, therefore, might potentially transmit infection to other mammals via unpasteurized milk.”

What role does IDT play?

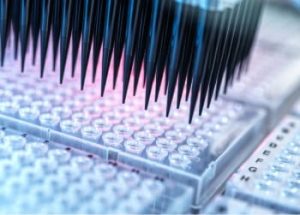

IDT recently launched the Avian Influenza Type A (H5) Primers and Probe Set, which specifically targets clade 2.3.4.4b. Manufactured in a certified template-free environment, this product is available to labs for research on the virus. The primers and probe set helps researchers involved in 2.3.4.5b identification and surveillance, research and understanding, vaccine development, and public health preparedness.

Click here learn more about IDT’s Avian Influenza Type A (H5) Primers and Probe Set.